LONDON — So, there you have it: 2017 was the year that finally broke the internet.

From Europe’s aggressive (some would say fanatical) expansion of digital privacy and hate speech rules to the rollback on December 14 of the United States’ net neutrality provisions, this year marks the end of an era.

Gone is the internet where people from Philadelphia to Paris pretty much had access to the same digital services. That basic tenet (the “world’ in the “world wide web”) is what made the internet the lifeblood coursing through our daily lives. It’s what was making countries’ borders increasingly meaningless and connecting people (for good and bad) in ways that seemed like science fiction just a few years ago.

The common global internet is now dead. In its place is something all together different: a Balkanized “splinternet,” where your experience online is determined by local regulation.

In 2018, the forces dividing the internet along regional or national borders are only likely to gain momentum, as governments worldwide reassert their control over digital forces that threatened to turn policymakers and politicians into bit players in a tech-centric world run by the likes of Google, Amazon and Facebook.

Instead of reining in the (many) excesses of the online world, regional digital rule-making threatens to derail the economic, societal and political advances of the internet age.

That Balkanization should worry anyone who (like me) believes that when harnessed correctly, the global digital revolution — like previous epochal shifts such as the Industrial Revolution — offers both new economic opportunities and a chance for people to become more engaged in public life.

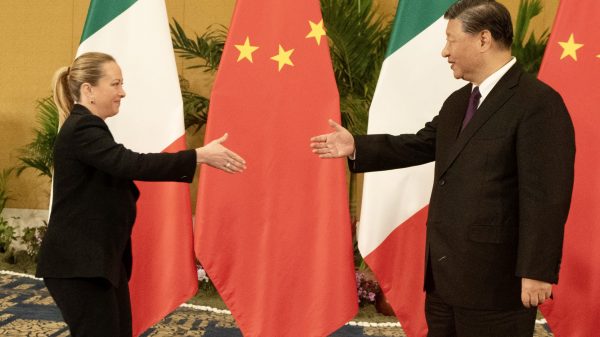

In part, governments’ efforts to reclaim control over the internet is only natural. But without better cross-border coordination between policymakers from across the globe — including China, where draconian internet laws still limit free speech and other fundamental rights — this mad dash to regulate could have the opposite effect than what’s intended.

Instead of reining in the (many) excesses of the online world, while protecting the underlying global structure of the internet, regional digital rule-making threatens to derail the economic, societal and political advances of the internet age.

Take net neutrality — the concept that all internet traffic should be treated equally, no matter if it’s a Google search, Netflix movie or Twitter rant.

On December 14, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission rolled back such provisions, in essence allowing telecom operators to charge digital companies for improved access to their telecom networks. Supporters of the changes say it won’t hamper innovation, even though critics (including Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the world wide web) say it’ll end the internet as we know it.

No matter the outcome, it’s going to alter Americans’ internet experience — for the good or bad, depending on your view.

By changing its stance on net neutrality, the U.S. is also setting itself apart from Europe, whose own net neutrality regulations still (mostly) insist that all internet traffic should be treated equally.

In the coming months, this diverging approach by arguably the world’s two largest digital markets (excluding China) about one of the underlying principles of the internet will start to bite.

A new service marketed to U.S. consumers, for example, may fall afoul of EU rules. Or a European could be offered a different version of a product sold to an American, solely because of each region’s contrasting approach to net neutrality. The result will be a regionalized internet experience that is fundamentally different to what is currently on offer worldwide.

Such online Balkanization isn’t just limited to changes in Washington, D.C.

In October, Germany passed some of the world’s most onerous online hate speech rules, including fines of up to €50 million for the likes of Facebook and Twitter if they consistently fail to remove illegal content from their digital platforms within 24 hours.

Other EU countries, notably France and Britain, also are mulling similar changes to force Big Tech to take greater responsibility for harmful or illegal material that appears on their sites.

And it’s not just the U.S. and EU that are pushing ahead with greater control of the internet.

Many on both sides of the Atlantic (including inside the tech companies) favor such a revamp. But Europe has gone significantly further to limit what can be posted online than in the U.S., where the First Amendment’s freedom of speech protections makes unilateral takedowns of content an impossibility.

This too is causing the day-to-day online experiences of Europeans and Americans to diverge, as content available in California may fail to make it through to others living in Catalonia. It’s hard to see how such digital splintering helps to spread ideas and foster debate between people around the globe.

And it’s not just the U.S. and EU — two of the world’s strongest (albeit, somewhat dysfunctional) democratic regions — that are pushing ahead with greater control of the internet.

Russia, Turkey, the Philippines and a growing list of other authoritarian regimes, as well as China and its existing “Great Firewall,” are similarly demanding their own versions of the internet. That includes forcing tech companies to store data held on local citizens in servers located inside these countries to strong-arming social networks to censor content critical of national leaders.

This is the current state of the digital world at the end of 2017.

Without a significant (and fast) reassessment of how the internet is governed worldwide, the coming year will likely lead to more of the same: greater national controls over an online realm whose global reach is quickly becoming a relic of the past.

Mark Scott is chief technology correspondent at POLITICO.

[contf] [contfnew]

Politico

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]

The post Goodbye internet: How regional divides upended the world wide web appeared first on News Wire Now.